SingaporeMotherhood | Parenting

September 2022

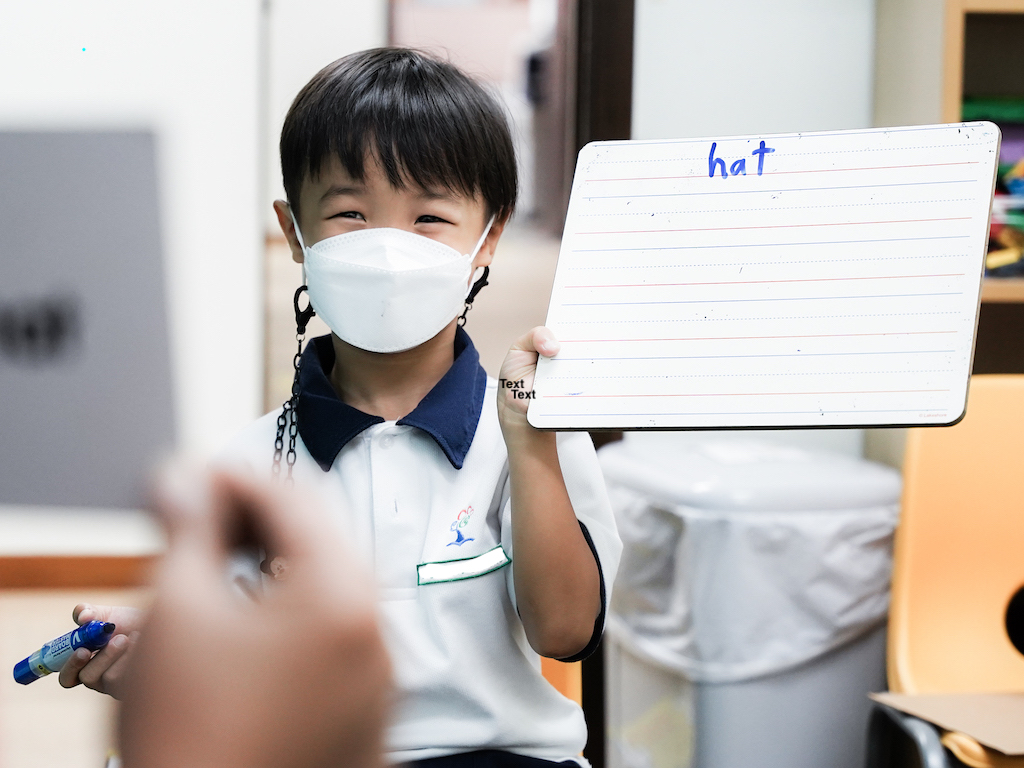

Navigating Emotional or Behavioural Challenges for Children with SpLDs

Specific learning differences or SpLDs are neurodevelopmental differences that are typically discovered and diagnosed in the first few years of formal schooling. Dyslexia, dyscalculia, dyspraxia, dysgraphia, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are examples of common SpLDs. While a child may have a single specific learning difference, co-occurrence of SpLDs is common.

These learning differences are independent of intellectual ability, socio-economic or language background. They can make it difficult for children to learn in one or more specific areas, such as focus and attention, communication, reading, written expression, and maths.

While there are no official statistics for the number of children with SpLDs in Singapore, the Ministry of Education has reported that there are about 25,600 students in mainstream schools who have mild learning needs including dyslexia, mild Autism Spectrum Disorder, and ADHD.

SpLDs, Learning, and Stress

In Singapore, where academic success and good grades are often emphasised, SpLDs in children can pose significant stress for them and their parents, especially due to the implications of SpLDs on learning.

It is not easy for children to see themselves falling behind their peers in school. Similarly, it can be demoralising for young children to find themselves among the last few in the academic race. Furthermore, parents may become overly preoccupied with the immediate implications of SpLDs — academic performance.

(See also: Teach your Child to Overcome the Fear of Failure)

While having an SpLD does not limit a child’s academic potential, the path to achievement is often harder and requires far greater (usually unseen) time and hard work. When parents only focus on academic performance and neglect to provide assurance, encouragement, and understanding for children with SpLDs, it exacerbates their feelings of self-doubt, frustration, anxiety, and sadness.

Signs that children may be struggling emotionally:

- Acting out

- Increased sadness or irritability

- Low sense of self e.g. thinking ‘I am stupid, right?’

- Increased anxiety, especially in academic situations

- Absence from class tests or school refusal, often citing physical symptoms like headaches or stomach pain

In addition to developing strategies and finding skills to help children with SpLDs compensate for their learning differences, it is important for parents to tend to their children’s emotional needs. If your child shows signs of emotional struggle, try to discover and understand their specific underlying issues.

Simply asking questions like “why did you cry?” may not yield much, as it is common for children themselves to not understand the cause of their behaviour. Instead, take an investigative approach. Ask your child questions from a factual angle, such as “what were you doing when you cried?”, to identify the trigger.

Speak to professionals who are already working with your children. Educational therapists, educational psychologists, Special Educational Needs (SEN) Officers and school teachers form an important network of support for any child.

Most importantly, even before your child exhibits signs of emotional needs, take steps to ensure that they remain happy and secure in the face of an SpLD diagnosis:

1. Make sure your Child Understands what SpLDs are

Adults with SpLDs have shared how liberated they felt when they learnt that their learning differences had nothing to do with their level of intelligence. Hence hearing explicitly from you, their parent, that their learning differences are just part of a normal variation in the population (like how some people are left-handers and some are right-handers) and have nothing to do with their intelligence, can be meaningful for your children.

(See also: Teach your Preschooler to be Inclusive & embrace Diversity)

2. Convey Positive Views of SpLDs to your Child

Start by getting comfortable with the diagnosis yourself. If you hold negative views towards having an SpLD, your child will probably feel the same. Use success stories of famous personalities with SpLD, preferably those whom they can associate with, to inspire them.

Singapore’s first Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew had dyslexia. He shared that he tended to make mistakes when speed reading, and coped with it by reading slowly. However, because he read slowly, he only had to read the material once for the information to sink in. His dyslexia might have brought him inconvenience, but he found a way to compensate. This made him better at comprehending the information than those without dyslexia.

If you do not feel confident about engaging your child in this, you can talk about it with your child’s educational therapist or educational psychologist. They are trained to explain SpLD to a child in a positive and comprehensible manner.

3. Be your Child’s Advocate

Equip yourself with SpLD knowledge and skills so that you can walk with your child on this journey. After all, no one understands your child’s needs better than you. Mainstream school teachers have to manage a class of 30 or more, so a child whose learning needs are not glaring may escape additional attention and support.

Ask your child’s teacher questions such as

- “Where is he/she seated in class?”

- “Does he/she have difficulty following lessons?”

- “How is his/her speed of work in class?”

- “Is he/she happy in class?”

At the same time, speak to your child to get feedback as teachers may miss out on their signs of struggle, especially if a child is reserved, and does not speak up.

Depending on your findings, your child may need to have more done to accommodate and support his or her learning. These can come in the form of access arrangements during examinations, additional classroom support, or withdrawal intervention support. These accommodations can go a long way in supporting your child’s learning and emotional needs.

4. Identify your Child’s Island of Competence

Not all children will end up being professional athletes or musicians, but every child has a skill they can build on. Find something that your child feels good about doing, that provides a sense of mastery and accomplishment, and give them space and time for practice. As your child’s talent grows, so will their level of confidence, self-esteem and happiness. This will help lay the foundation for a happy and successful life — one that goes beyond academic achievements.

This article was contributed by Dr June Siew, Head of the DAS Academy, which trains parents, caregivers and educators with skills to support learners with dyslexia and other commonly co-occurring Special Educational Needs (SEN).

Photos: Dyslexia Association of Singapore, unless otherwise stated

All content from this article, including images, cannot be reproduced without credits or written permission from SingaporeMotherhood.

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, and Telegram for the latest article and promotion updates.