Angelica Cheng

Active Member

Relevant Q & A on the Quora website:

www.quora.com

www.quora.com

www.quora.com

www.quora.com

singaporenewslive.com

singaporenewslive.com

The risk of Down syndrome for a woman in their late 30's, around 37 to 39 years old, hovers around 0.5% or 1 in 200, according to the attached tables and charts. Hence, women in this age group have to be really unlucky to have a Down Syndrome baby, which is like hitting the jackpot.

At the same, it is highly expensive to do PGS / PGT-A. It roughly costs about 50% of an IVF / ICSI cycle. Hence, if the treatment cycle was to cost $10,000, adding PGS or PGT-A would bring the costs up to $15,000.

Is it worthwhile taking a calculated risk of not doing PGS / PGT-A to cut costs and save money for further IVF attempts? After all, more than one IVF attempt is usually needed to achieve success, and it would be financially exhausting to do PGS for every IVF cycle.

I am of the opinion that the Ministry of Health (MOH) in Singapore considers PGS / PGT-A not cost-efficient. Or else why are they currently being so restrictive on allowing the widespread application of PGS / PGT-A in Singapore?

After all, one can always do much cheaper prenatal testing after getting pregnant to check for Down syndrome.

Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) is now available. This is much cheaper than PGS / PGT-A and involves sampling of the baby's cells within maternal blood of a pregnant woman, with minimal risks to the unborn child. Please refer to the following websites:

https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/primer/testing/nipt

What Does NIPT Test For and How Accurate Are Results?

I would love to hear your opinion.

How can I do preimplantation genetic screening (PGS or PGT-A) in Singapore?

Answer: Currently, the Ministry of Health (MOH) of Singapore only allows a strictly-controlled clinical trial of PGS at selected government hospitals (NUH, SGH and KKH). Women undergoing IVF or ICSI must meet specific criteria to qualify for the PGS clinical trial, such as >35 years old, history ...

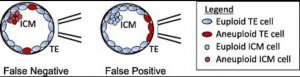

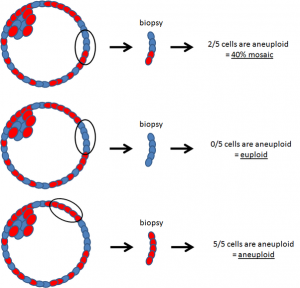

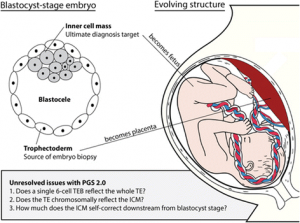

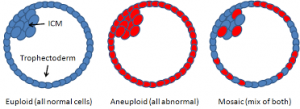

What are mosaic embryos and how do these affect the success rates of IVF or ICSI with preimplantation genetic screening (PGS / PGT-A)?

Answer: Mosaic embryos are embryos that have a mixture of genetically normal (euploid) and abnormal (aneuploid) cells. These are often tested to be genetically abnormal by PGS / PGT-A, but in fact can give rise to normal healthy births. As seen in the attached diagrams of a blastocyst stage embr...

Avoiding the moral dilemma and emotional trauma of Down syndrome abortions by mainstreaming IVF genetic testing for older women - Singaporenewslive.com

by Dr Alexis Heng Boon Chin Down syndrome is a genetic condition caused by an extra copy of chromosome 21, which is characterized by impairment of mental and physical development, together with increased predisposition to certain medical conditions such as congenital heart defects, diabetes, and...

singaporenewslive.com

singaporenewslive.com

The risk of Down syndrome for a woman in their late 30's, around 37 to 39 years old, hovers around 0.5% or 1 in 200, according to the attached tables and charts. Hence, women in this age group have to be really unlucky to have a Down Syndrome baby, which is like hitting the jackpot.

At the same, it is highly expensive to do PGS / PGT-A. It roughly costs about 50% of an IVF / ICSI cycle. Hence, if the treatment cycle was to cost $10,000, adding PGS or PGT-A would bring the costs up to $15,000.

Is it worthwhile taking a calculated risk of not doing PGS / PGT-A to cut costs and save money for further IVF attempts? After all, more than one IVF attempt is usually needed to achieve success, and it would be financially exhausting to do PGS for every IVF cycle.

I am of the opinion that the Ministry of Health (MOH) in Singapore considers PGS / PGT-A not cost-efficient. Or else why are they currently being so restrictive on allowing the widespread application of PGS / PGT-A in Singapore?

After all, one can always do much cheaper prenatal testing after getting pregnant to check for Down syndrome.

Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) is now available. This is much cheaper than PGS / PGT-A and involves sampling of the baby's cells within maternal blood of a pregnant woman, with minimal risks to the unborn child. Please refer to the following websites:

https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/primer/testing/nipt

What Does NIPT Test For and How Accurate Are Results?

I would love to hear your opinion.

Attachments

Last edited: